Purple Paonia Paralyzer – The Best Ever

by Marcello Cabus

In 1971, despite being illegal, pot could be found nearly everywhere in the U.S. Some of it was good, but most of it was smuggled in from Mexico. Those of us involved in meeting the expanding demand for pot were always on the lookout for better product. Since the late ’60s, a trickle of hashish, the concentrated and potent resin, had begun to show up in places like Boulder, Colorado. So much more potent than pot, it was prized and celebrated when it showed up, coming from places like Nepal, Lebanon, and especially Afghanistan, where it had been cultivated for centuries.

Illegal growing operations had begun to flourish in remote rural places around the nation, and as any gardener or farmer will tell you, the quality of the plant begins with the seed and the climate in which is grown. Pioneering growers were beginning to turn out better quality product, but not having access to high quality, original, and native cannabis seeds hindered them.

I want to share with you the story of how a trip to Amsterdam to sell Orange Sunshine LSD led to my bringing back a stash of seeds that would help birth a legendary pot known as Purple Paonia Paralyzer in Paonia, Colorado.

In 1971, I owned the Cotangent, a small fashion-clothing store on the hill in Boulder, Colorado. That year, I traveled to Europe with my wife Rosie, our one-and-a-half-year-old son Mikeljon, and Marina, a Dutch Indonesian beauty as our nanny. We entered Holland with a brand-new Volkswagen bus and 30,000 hits of Orange Sunshine acid I planned to sell to the locals. Unfortunately, Amsterdam had turned sleazy by the time we arrived, and I had a bad trip there when some street thugs tried to rob me. That convinced me to leave Holland, Muy Pronto, for Copenhagen, Denmark.

While walking on Stroeget, the walking street of Copenhagen, I was suddenly seized and lifted up into the air. The villain was Otis Taylor, a dear old friend of mine from Denver, Colorado. Otis is a great blues performer. In 2004, Otis and Etta James were named the “Best Blues Entertainers by a Living Blues readers’ poll.” Otis had been living in Europe working on his music, and introduced me to the high end of Danish hip society—the musicians, the artists, shop owners and, of course, the drug dealers.

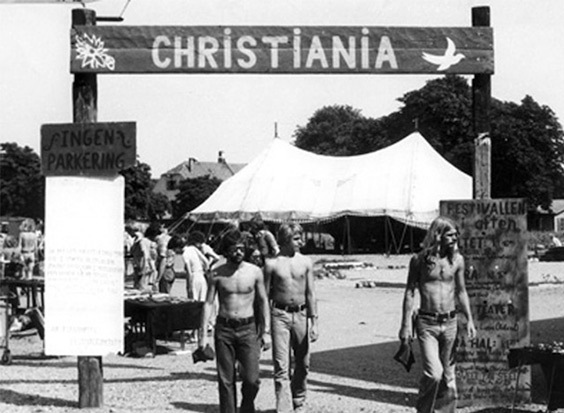

A week later, my small family and I were living on Bornholm, a Danish island that is a12-hour ferry ride from Malmo, Sweden. We had been invited by Jim Manning, an American who owned a leather store called the Bit Ov Sole in Copenhagen, to visit his farm. During the next few months, we went back and forth between Bornholm and Denmark. We eventually parked the VW bus in Christiana, the free city inside Copenhagen where hippies had completely taken over the former military buildings. Their commune’s central government allowed no police presence. Coffee houses, vegetarian restaurants and crash hostels occupied the buildings the commune had appropriated. It was complete harmony with one hand waving free.

Christiana was even more radical than my hometown of Boulder. While peddling my LSD in Denmark, I ended up at a house off Friedens Ark near Pusher Street where about 12 people, mostly girls, lived. The house was the end point of a smuggling operation by some Danes. Unloading their drugs from false-bottom suitcases and special-built vehicles, the traders unpacked, disassembled, and repackaged their psychic condiments mostly for sale to locals, but some were from Scandinavia and some big buyers came from Eastern Europe. At that house I met Pimm, a Danish smuggler, who also kept a house in a small village outside of Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. A smuggler takes something of lesser value to a faraway place where it increases in value and creates a bigger profit. Pimm’s profitable business was walnuts. He would take apart walnuts in Afghanistan, replace the nut with a gram of hash, glue the shells back together, and export them to Denmark by the case. I appreciated his ingenuity, but I told him of a smuggling technique I had in mind that involved exotic animals and false-bottom cages.

Five days later, he and I flew to Kabul, Afghanistan. Pimm kept a vehicle in Kabul and we drove north to Mazar-i-Sharif. Two days later, we left for the Hindu Kush region near Pakistan. Pimm spoke Pashto and knew how to greet and pay baksheesh to the right tribal leader. We traveled unmolested through Afghanistan during that time with a photo of their leader on the dash of our car.

We met some mujahedeen and drank tea with them in their tents. They introduced us to a farmer/grower. Pimm bought hash from him and I traded my parka to the son for 10,000 Afghani Indica marijuana seeds. The Hindu Kush region compared to the high desert of Colorado — hot days, cool nights, crisp air, and the mountains that seemed so like Colorado’s that I came up with an idea to take the seeds back to my own hemisphere. The valleys of the Hindu Kush resembled the Paonia Valley on my side of the world.

The Hindu Kush region compared to the high desert of Colorado — hot days, cool nights, crisp air, and the mountains that seemed so like Colorado’s that I came up with an idea to take the seeds back to my own hemisphere.

I am not a very technical or scientific person. Taking the tea bag out of hot water is about my speed, but I had a feeling. Even so, I helped Pimm design and manufacture the cages to hold both animals and hashish. Pimm shipped my seeds with his walnuts in the cages. I left him in Kabul to his adventures and departed to my own adventure in Nepal. Before I left, I went to the local market and bought a sheepskin coat and bags of spices. I put about a hundred seeds in one cardamom spice bag. Rosie took the bags back with her to Colorado.

Six months later, I shipped the majority of seeds from Denmark back to Colorado inside a stuffed animal, along with two hardcover copies of Hans Christian Andersen stories. I sent it to a mailbox on Sugarloaf Mountain, an address of an old friend of mine who died in Vietnam. One of my staff lived across the road and he would pick up the package to complete their journey. Truthfully, the seeds were an afterthought, not on top of my priority list.. However, I knew nothing of genetics or growing. I was just a marketer, so I call the noble experiment that took place over the next three years “happenstance.”

I bought a farm with the Boogie commune, 20 acres outside of Hotchkiss where my family and the commune lived on Sunshine Mesa. The boogies made leather coats and I sold them in the Cotangent. I never spoke to anyone about the seed.

By now, commercial growers were moving into the area since the land was cheap and came with good water rights. The locals accepted the longhairs unconditionally. The cops used to post signs on the patches they busted that read, “This time your grass, next time your ass.” It’s my opinion that grow operators have a completely different mindset than others in the marijuana trade. They are little shifty and often flip the script and change the deal, maybe because of the long time it takes to go germination to counting Benjamins. If you touch, pamper, and talk to the plants and do those actions repeatedly in your mind, your perceptions change over the years.

Since I did not allow growing on my property, Rosie and our friend Monte grew the hundred seeds from the cardamom spice bag in several locations around Paonia and Hotchkiss. The only plants we personally grew came from those hundred seeds. I called the resulting pot, “Do not drive a motor vehicle.” I selected a group of growers, threw a party at harvest time, and invited that group. When the harvest came in the valley, it was a wondrous time. Everyone was blitzed.

The bulk of the seed was given away to growers from all over the country; it went to Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Indiana and all over the valley. It was always my hope that these giveaways would result in reciprocal trade, though sometimes it was and sometimes it wasn’t. I never realized the impact the seed had until I started working on my book, Pioneers of Leisure. Delta County where Paonia was known as one of the poorest counties in Colorado, but the seed changed the dynamics of the families. The families now made enough money to live for a year and what used to be a supplemental income became their primary income. One year a family might be living hand-to-mouth and next year they were buying acreage. Long-term local residents grew wealthy. Of course, as usual, along with the good came the bad—people riding along irrigation ditches looking to raid someone’s patches.

Paonia now is a destination for weed connoisseurs worldwide. The seed I had brought back from Afghanistan became known as Purple Paonia Paralyzer. Uncle Butch Eisenmenger, a Cannabis Cup judge, told me it was the strongest herb he had ever seen. The seed had taken on its own destiny. I have often thought if I had altered the natural flow, I would have destroyed the mystique it still enjoys. A legend was born.

References:

https://www.outfrontmagazine.com/trending/out-front-strain-of-the-month-purple-paralyzer/

http://westernslopenews.com/history/2014/5-1/pg7/pg7index.html

https://www.denverpost.com/2014/07/03/champagne-of-pot-is-possible-in-paonia/

https://www.hcmagazine.com/paonia/